Hidden Morse Code in Tubular Bells

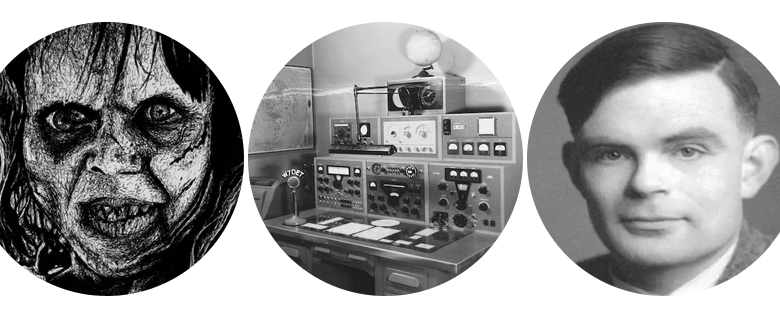

The link between The Exorcist, Amateur Radio and Alan Turing.

A quick look at how the movie The Exorcist from 1973 has links to the late great Alan Turing via Mike Oldfield’s album Tubular Bells, Scotland and Amateur Radio. It’s Halloween so thought why not throw some horror into the mix.

When Mike Oldfield recorded Tubular Bells in 1973 he had no idea that his first Virgin Records album would be chosen as the soundtrack to The Exorcist later that year. He also didn’t know that the Virgin Records recording had the unintended consequence of hiding a secret message that dates back to 1926, shortly after the First World War.

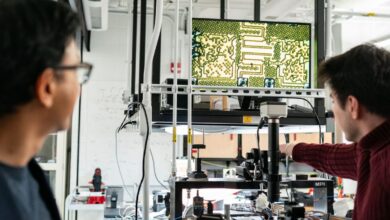

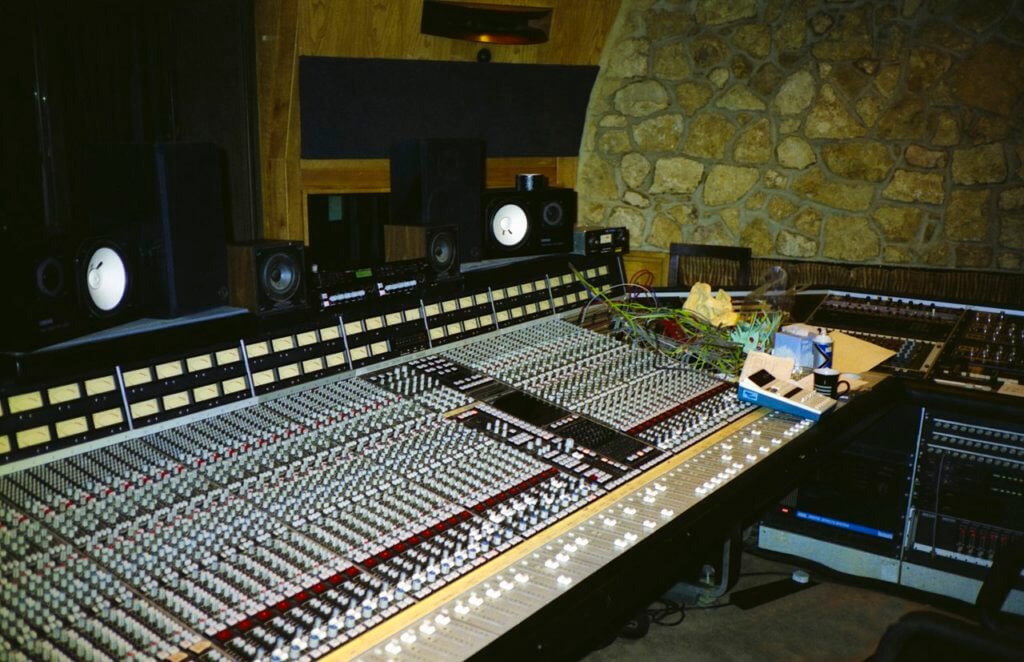

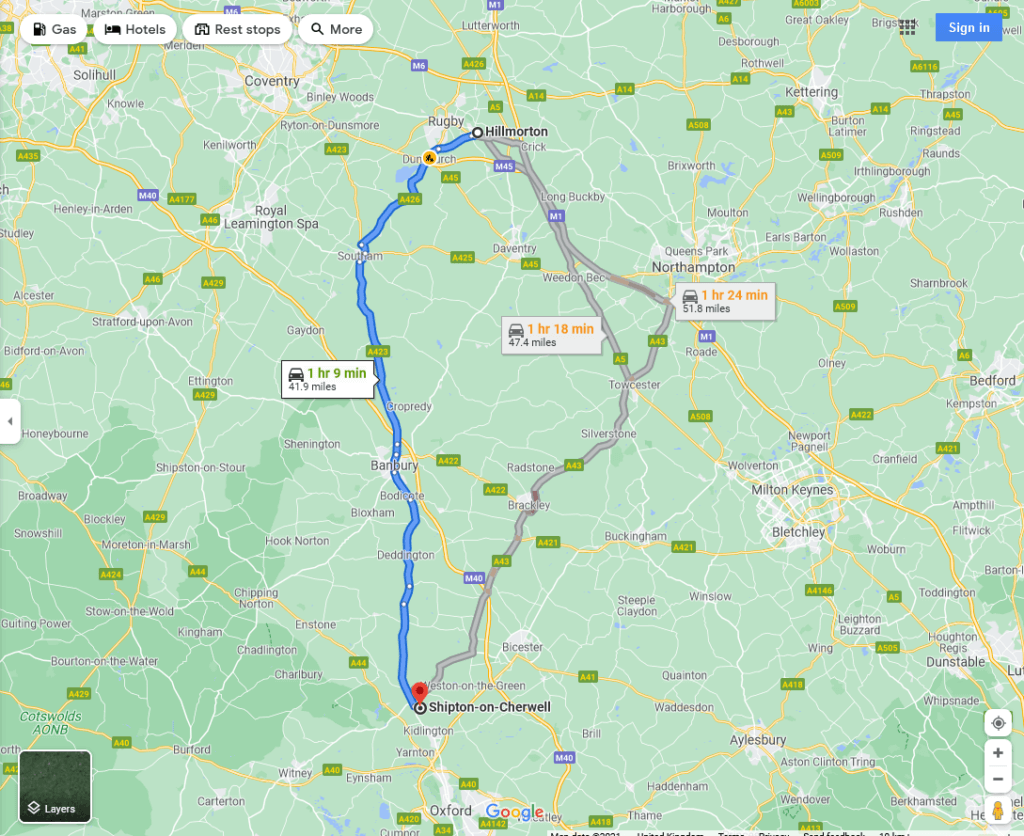

Tubular Bells was famously recorded at The Manor Studio owned by Richard Branson and used as a recording studio for Virgin Records. The building is located in Shipton-on-Cherwell, England. Mike was given one week to record the album, during which he played almost all the instruments himself.

The album initially struggled to sell. Then, later in the same year, it was chosen as the soundtrack of the movie The Exorcist. It experienced great success and has sold more than 15 million copies worldwide.

Here in this very studio, completely unknown to the engineers at the time, they accidentally picked up a radio signal from a nearby transmitter and kept it forever on the Tubular Bells album.

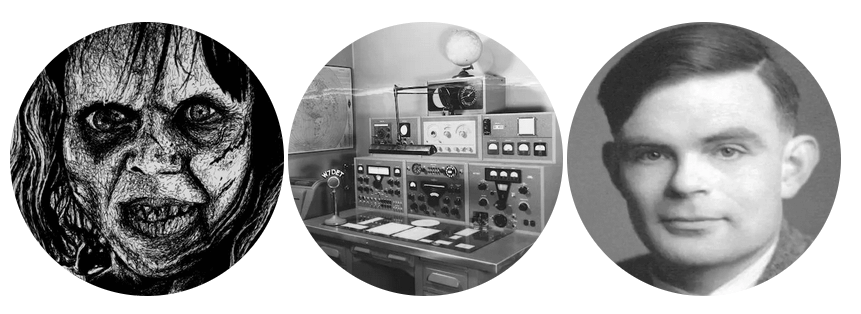

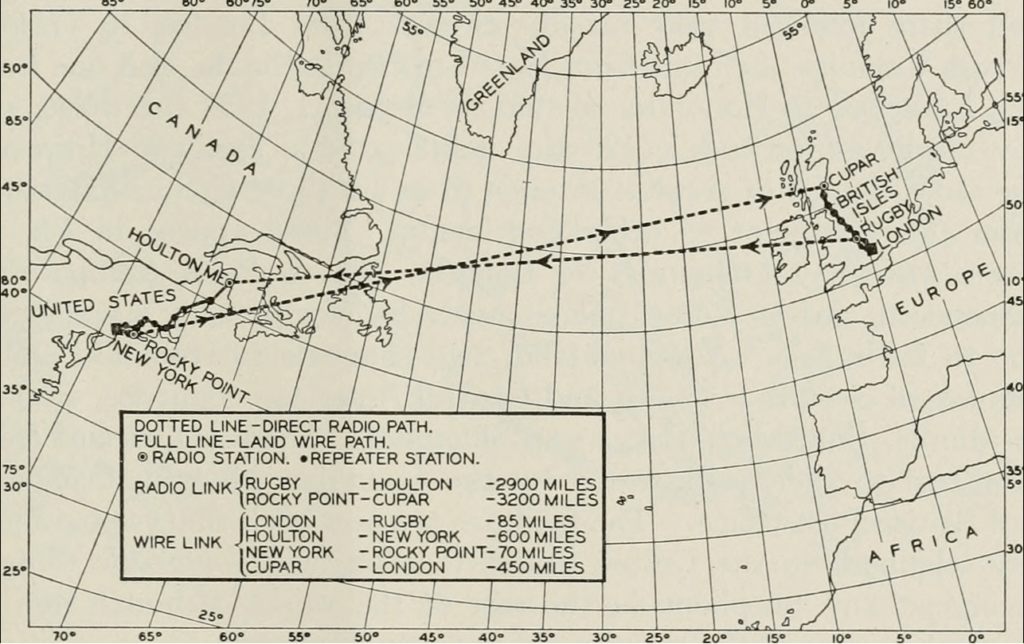

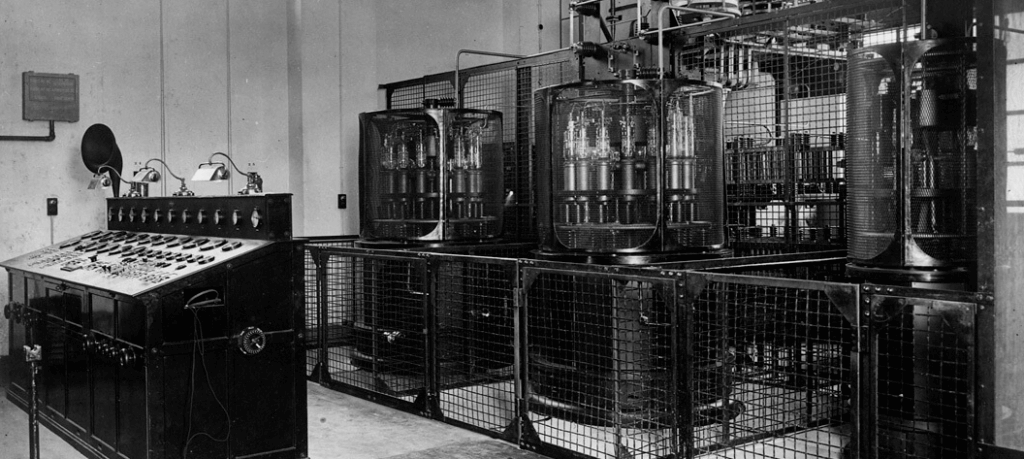

About 37 miles north of the studio near Rugby, in a small suburb called Hillmorton, a very large radio transmitter was built after the First World War to link Great Britain with other parts of the Empire. in Britain. It was originally used to send telegraph messages to the Commonwealth as part of the Imperial Wireless Chain. After the 1950s this transmitter was used for transmitting messages to sunken submarines and therefore operated at Very Low Frequencies (VLF). In 1927 a second transmitter was added to enable the first transatlantic commercial telephone service between England and the USA.

The first Rugby transmitter operates at very high power at 16 KHz, which is as far as the radio spectrum goes at very low frequencies. Very low in fact being within the 20 Hz – 20 KHz range of human hearing. Now, let’s be clear here – electromagnetic radio waves and sound pressure waves are very different. The human ear cannot detect electromagnetic waves of any frequency, however, electronics intended for audio can also detect radio waves because all they are sensitive to is voltage and it does not matter what the voltage generator.

In the case of a microphone (audio) that is the electrical energy generated by the moving diaphragm sent by the cable. In the case of an antenna (electromagnetic wave) the electrical component of the radio signal induces a voltage in the conductor. In both scenarios the electronic equipment at the end of the wire only sees voltage. As long as it is sensitive to the frequency of the signal it makes no difference where said signal originates.

I’m sure the technically astute amougst you can see where this is going. First, let’s see where there are two places on the map.

As the crow flies these two locations are 37 miles from each other. That may be going too far but let’s look at the scale of the shipping station we’re talking about.

I did not find any details about the power output of this station (actually it consists of 57 transmitters in total) but based on the same transmitter (Anthorn Radio Station) it is safe to assume that a 16 KHz transmitter will be tens if not hundreds of kilowatts. Given how narrow the bandwidth of CW signals is, compared to say something like TV, that amount of power is huge.

That’s enough background, now let’s see what happened.

The Rugby Radio station transmitter will always announce his ID (callsign) via Morse Code. This is supposed to be an automated process that runs 24/7 unless a particular message needs to be sent, in which case the constant transmission of the ID will temporarily stop and the message will be sent instead.

Due to the proximity of the Manor Studio to this large transmitter and the fact that it transmits within the frequency range of an audio recording, the signal was picked up by several pieces of studio equipment. As mentioned, although the human ear cannot detect electromagnetic waves, electronic equipment – even those intended for audio – can. It is similar to placing your mobile phone near a speaker and hearing the random beeps of interference it can cause. The video at the bottom of this page shows how a person can use a standard computer audio interface to receive VLF radio signals. Something in the studio was sensitive enough to record the morse code being transmitted and it was stored forever on the Tubular Bells album. No one knows exactly what’s picking it up – it could be a microphone or guitar pickup – although given how regularly it appears throughout the album it’s possible it’s a mixer or the recording equipment itself , perhaps through unshielded cables that serve as antennas.

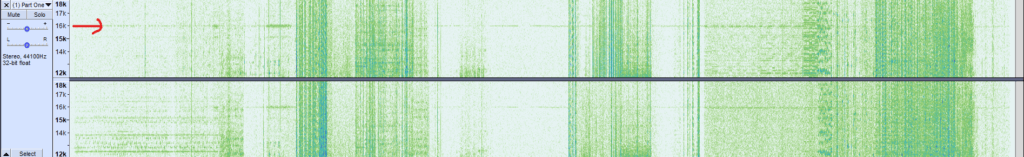

It was originally discovered by a chap from Austria named Gerhard Kircher. He tried a spectrum analyzer and noticed a strange signature at 16 KHz. Let’s look at this using Audacity’s spectrogram feature.

You should see a faint horizon line at exactly 16 KHz running across the track. This is of course the ‘unknown signal’ which is clearly out of place.

I used a lossless FLAC copy of the CD album from 2003 to see it. It’s possible that many of these are missing from lost copies, such as MP3s, though I haven’t tested that yet.

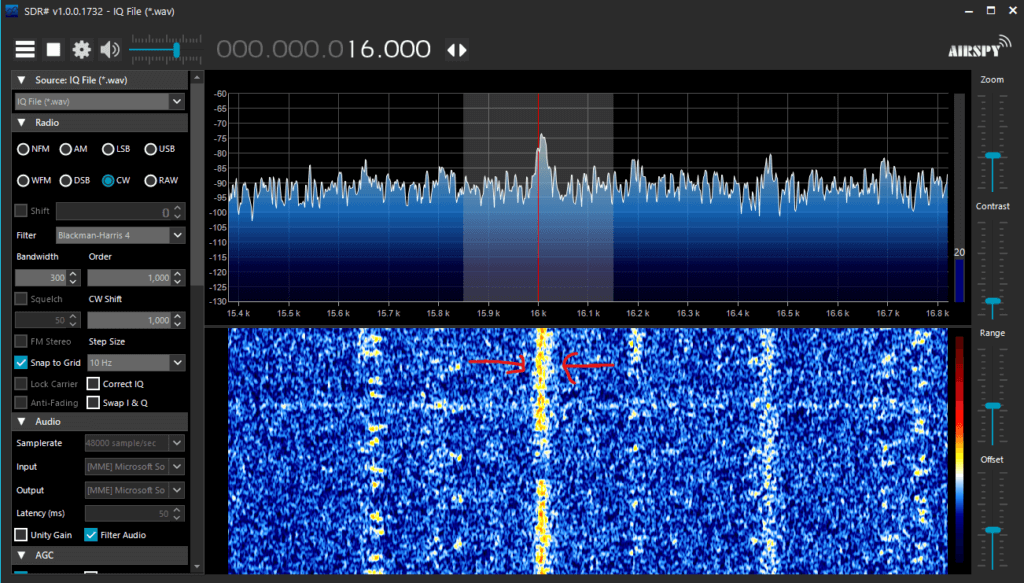

To actually hear this signal we need to run it through some software to center the frequency, demodulate and use a narrow band filter. By setting the center frequency of the transmitter (16 KHz) we can demodulate the CW carrier. To do this I use SDR# (pronounced sharp). When we load the file in this software we can clearly see the Morse Code signal.

What we have here is a wave file loaded and two important settings selected. First set the center frequency to exactly 16.0 KHz and second set the modulation to CW (typical single side band) with a bandwidth of 300 Hz. When you adjust the frequency you will hear the morse beep tone going up and down.

The yellow line, with clear gaps in it, is the Morse Code transmitted by the Rugby Radio Station. The first question you might be thinking is – but how do you know?

Here is a recording of the output from SDR # (direct link to the file)

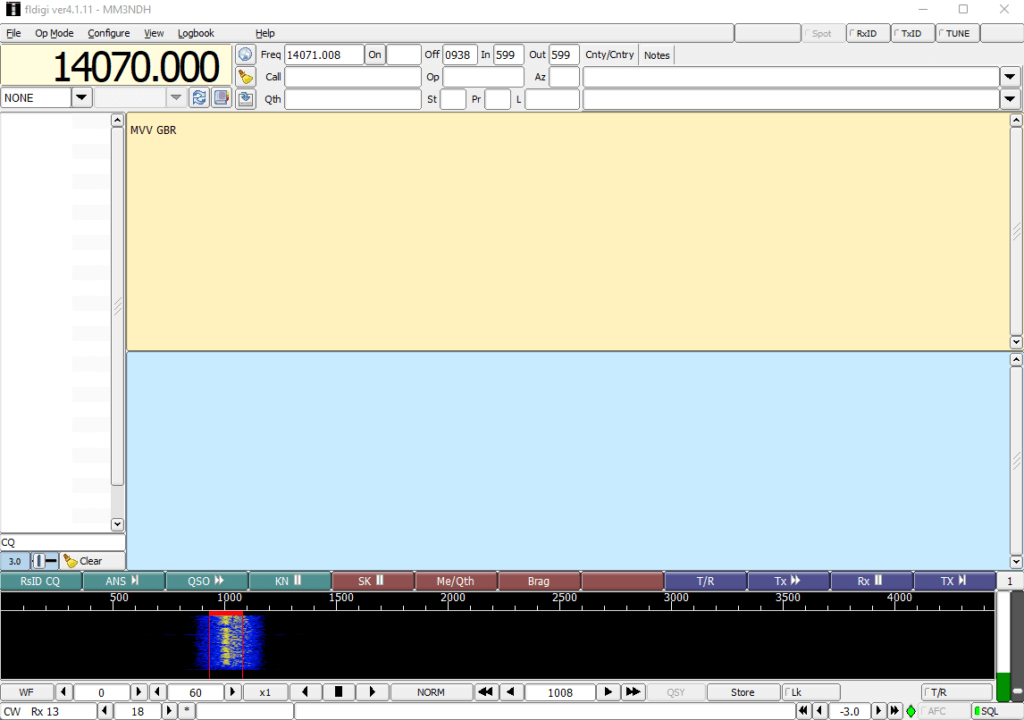

Although amateur radio is a hobby of mine I don’t know morse code by heart. Sure, I can only look it up but thankfully there is software that can help us. Let’s run this output, using a virtual audio cable from SDR#, through FLDigi and see if it can decode the signal.

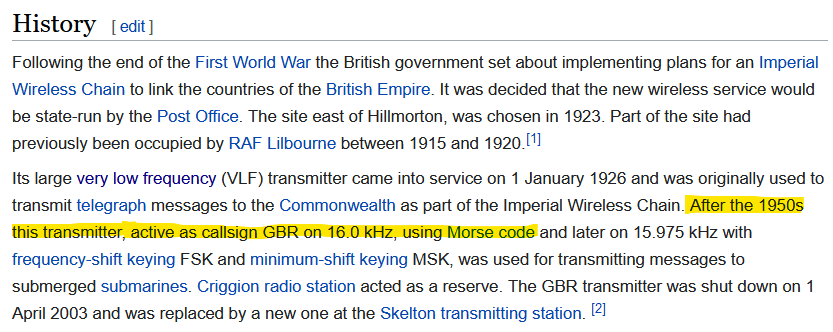

Interesting – it is decoded as ‘MVV GBR’ at about 1 KHz. Now let’s see what the callsign of Rugby Radio Station is. From the Wikipedia page:

It’s cold! We know that this station was active as ‘GBR’ at the time the Tubular Bells were recorded and it happened to be on the same frequency. I’d say that’s pretty damn conclusive.

The decoded morse is actually slightly wrong – instead of ‘MVV’ at the start it should be ‘VVV’ but that in FLDigi is not 100% accurate. Anyone who knows morse can confirm what you heard as ‘VVV GBR’.

We can tell that “VVV” is a generic prefix of some kind and “GBR” is an acronym for “Great Britain Rugby”.

The GBR transmitter was closed on 1st April 2003 and replaced by a new site known as Skelton transmitting station. The old building is became a school.

Depending on which piece of equipment is picking up the transmission there may be several albums with this signal recorded on them. Here is one partial list of albums Recorded at The Manor Studio. I suspected it was something specific to this album but wanted to be proven wrong.

If you scroll back and look at the old Transatlanic Radio Network map you will see that Rugby is one of three UK stations along with London and Cupar. The Cuper station is responsible for receiving signals from Rocky Point in the states, about 3200 miles away.

Cupar (Fife) station in Scotland also became part of the so-called “Y” service. It was part of an effort to intercept and direct the search for enemy radio transmissions during the First and Second World Wars, including Enigma encrypted messages, which as we know all of which Alan Turing finally cracked. The station at Cupar is officially known as GPO Transatlantic Radiophone Station Kembeck (a small village outside Cupar). Receivers like The National HRO The receiver of the communication is usually at such stations.

During World War II many Amateur Radio operators were enlisted as “Voluntary Interceptors” to aid the effort because they often had the necessary skills to operate the equipment and knowledge of radio communication in general. .

The skills of all the radio operators including several hundred women and men helped collect enough encrypted messages for Turing’s amazing machine to break the code. Apart from the legacy of cracking the Enigma code, the computer scientist also left us the concept of Turing Completeness. This is when a computer system can recognize or decide on other sets of rules to manipulate data. Turing completeness is used as a way to express the power of such a rule set to manipulate data. Almost all programming languages today are Turing complete.

So there we have it – a somewhat awkward but hopefully fascinating link between The Exorcist, Tubular Bells, Scotland, Amateur Radio and the great Alan Turing.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tubular_Bells

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y_service

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rugby_Radio_Station

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthorn_Radio_Station

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Manor_Studio

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kemback

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_completeness

https://www.coventrytelegraph.net/lifestyle/nostalgia/classic-album-hidden-code-3109812

The following YouTube video was the initial inspiration for this blog post (sent to me by Brian – GM8PKL) and contains a lot of information around using a standard sound card as a VLF reciever. It shows how a device intended for audio can actually receive RF.

2025-01-23 23:19:00