The History and Popularity of Venn Diagrams Outside of Math Explained

In his book The Mathematical Universe, Mathematician William Dunham wrote about John Venn’s legacy, the Venn diagram, “None in the long history of mathematics has been better known below.” While Venn diagrams may not solve anything long open problemssurely these connecting rings deserve more credit. Their underrepresentation in group relations explains their enduring appeal in classrooms, infographics and Internet memes.

Not just visual aids, Venn diagrams help us solve everyday logic problems, and they can raise surprising geometric questions. Have you ever seen a fit Friend diagram with four overlapping circles? No, because it is impossible. Venn himself discovered this and came up with a clever fix, but it only created a deeper geometric puzzle that mathematicians are still studying today.

Venn debuted his diagrams in 1880 as a way of imagining contemporary developments in logic. They immediately found an application of close relevance branch of mathematics called set theorywhich focuses on collections of objects. Venn diagrams usually consist of overlapping circles, each of which represents some set of elements, (for example, classics or Broadway shows). The overlapping region between the two circles contains elements belonging to both sets (for example, “cats”). Like use scatter plots of statistics or draw geometry shapes, SEEING a person’s problem often explains it.

In support of science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription you help ensure the future of meaningful stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

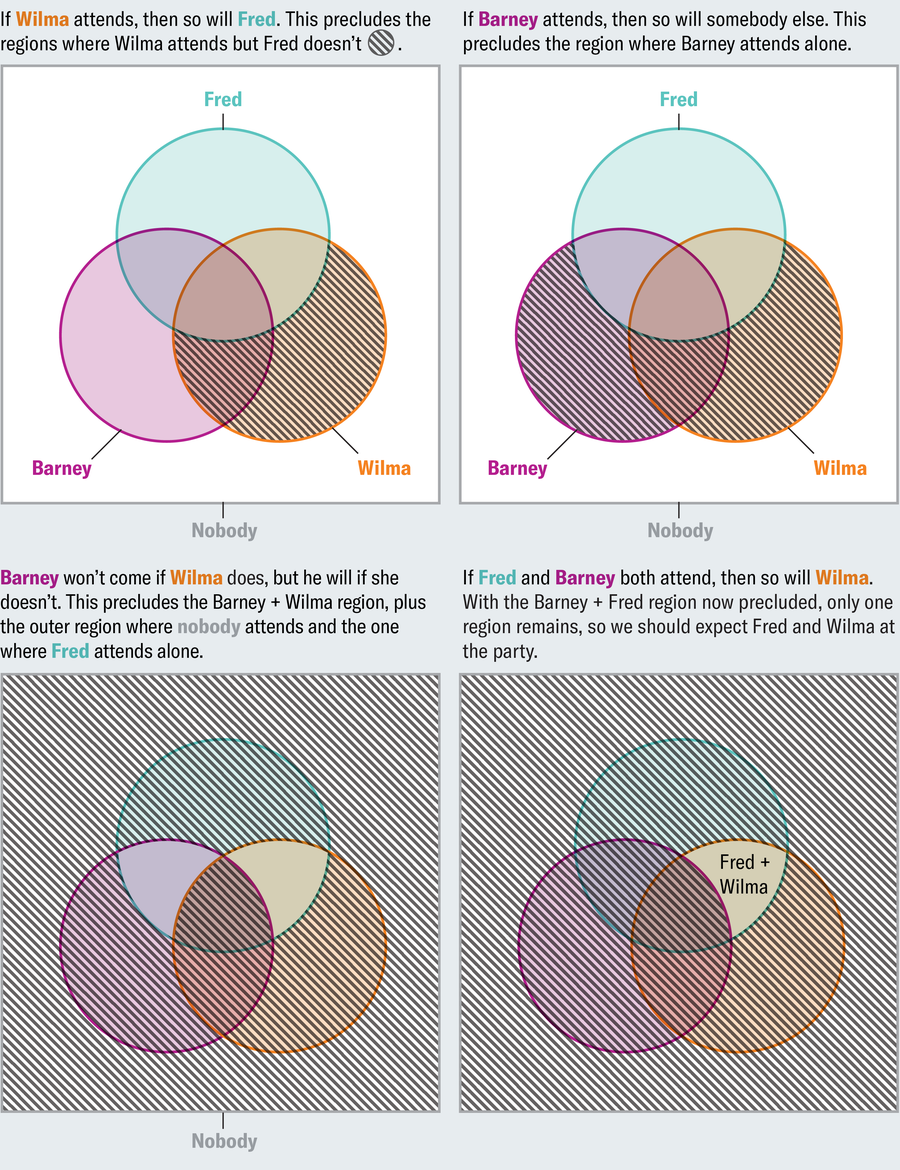

Imagine you’re planning a dinner party and navigating your friends’ preferences. If Wilma attends, Fred will also attend. When Barney attends, so do the others. Barney doesn’t come when Wilma comes, but he goes when she doesn’t. If Fred and Barney both attend, so will Wilma. Who should you expect to show up? This poser is difficult to solve if we are only given text. A Venn diagram provides a systematic way to visualize and solve this. Each statement restricts several possible outcomes, which we indicate by shading the corresponding regions of the Venn diagram.

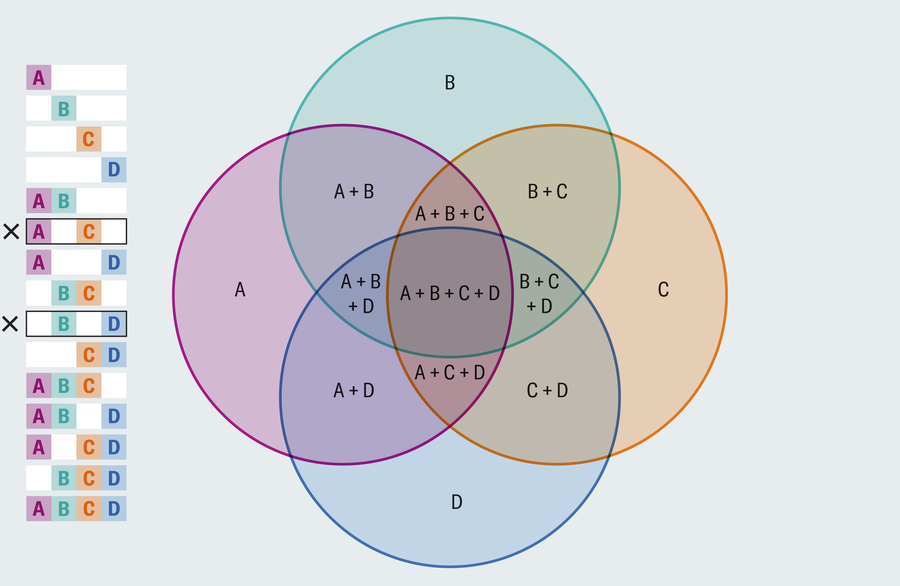

Most Venn diagrams you’ll encounter depict two or three overlapping circles, but what if you have four or more sets to consider?

Do you see the problem? There is no region where only A and C overlap that does not also include another region, and the same is true for B and D. An accurate Venn diagram depicts each combination of intersections. Rejiggering the layout doesn’t help. Each four circle drawing has the same error.

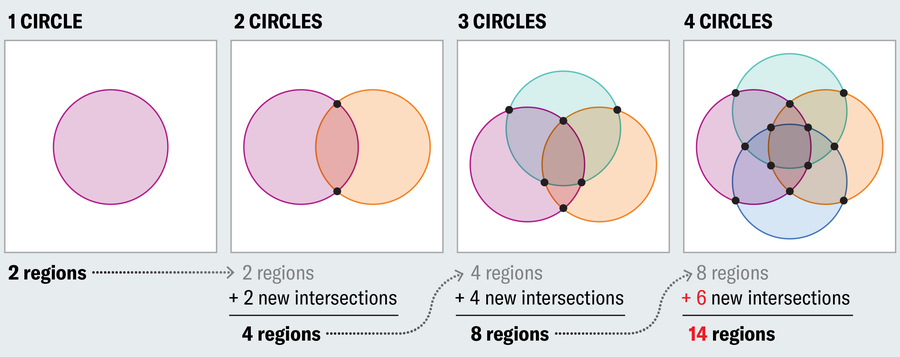

To see why, start with a circle and note that it creates two regions—interior and exterior. If we add a second set of elements (a new circle), we double the possibilities, so we need to double the number of regions (first set, second set, same set and none set). The only way to do this is to intersect the second circle with the first two points (touching only one point results in only three regions: first set, second set or none). This trend continues, where each new circle must double the number of regions if we want to represent all the logical possibilities. But the number of new regions does not exceed the number of new ones intersectionsand a new circle can intersect existing circles at only two points each. This is useful when adding a third circle because we need to add four regions, and the new circle can intersect two existing circles at two points each for a total of four new intersection points. But it breaks down in the fourth circle, where we need eight new regions but can only gather six new intersection points.

Of course, we don’t need to limit ourselves to circles. We can easily trace a wiggly loop through a three-circle diagram so that it can carve out the required number of regions, but lose the elegance of the diagram. Four intersecting spheres can also represent the correct number of regions, but three-dimensional visuals are difficult to parse. John Venn recognized the inadequacy of circles, so he proposed ellipses to represent four sets.

Mount Amanda; Source: “Venn Diagrams and Independent Families of Sets,” by Branko Grünbaum in Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 48, No. 1; January 1975 (references)

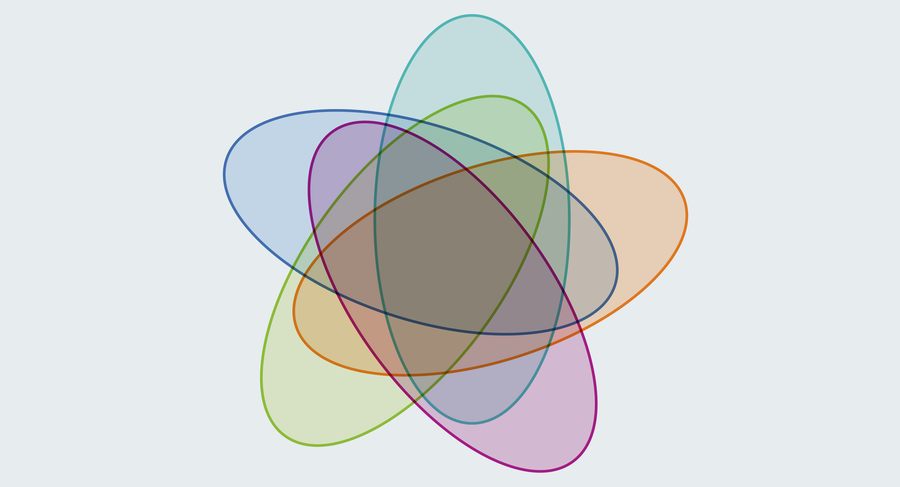

Unlike circles, two ellipses can intersect four score. It overcomes the limitations of circles but only temporarily. Ellipses work for four and five sets before failure in the same way circles do. As the sets grew, we needed more exotic shapes to depict them.

One could reasonably argue that beyond four sets of elements, Venn diagrams lose their utility. The four-ellipse image is a bit messy. Perhaps for the five additional sets we should abandon the visual representations. But utility does not animate the mathematician like beauty and curiosity. Although Venn diagrams were originally applied to logic and set theorythe four circle conundrum raises an interesting question in geometry. That seed blossomed into a fascinating investigation of geometry in the Venn diagram that continues today.

Venn and his successors believed that ellipses could not describe all 32 regions required for a five-set diagram. It wasn’t until 1975 that the mathematician Branko Grünbaum proved them wrong by example:

Mount Amanda; Source: “Venn Diagrams and Independent Families of Sets,” by Branko Grünbaum in Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 48, No. 1; January 1975 (references)

Note also that Grünbaum’s diagram exhibits pleasing rotational symmetry. Spinning it one-fifth of a full turn causes it to return to itself, without changing its original shape. Common two- and three-circle Venn diagrams share this property. Rotate the two-circle Venn diagram by 180 degrees (or the three-circle one by 120 degrees), and it looks the same. But the four-ellipse diagram has no rotational symmetry. Can that be fixed? What do two, three and five have in common that four do not have?

In 1960 an undergraduate student at Swarthmore College, David W. Henderson, answered this question with a startling discovery (Stan Wagon and Peter Webb filled in some gaps later): A rotationally symmetric Venn diagram is possible only if the number of sets is a prime number—a number that is only divisible by 1 and itself, like 2, 3 and 5 but not 4. Henderson only showed that a prime number is needed in sets, not that you can always design a symmetric Venn diagram for each prime number. Thus began a competition to find more and more examples. Here’s a wild look 11-set Venn diagram from Peter Hamburger.

Mathematicians at the University of South Carolina the question is settled in 2004 by showing that rotationally symmetric Venn diagrams exist for every prime number of sets. If you think this is the reason mathematicians pack up their pencils and take a break from studying Venn diagrams, then you’re wrong. Instead the community raised their aesthetic standards, looking for figures to match more refined properties.

Our opening quote argues that Venn diagrams are overrated. Even those who agree must admit that they have a unique appeal. Take the sets of interesting topics in logic, in geometry and in visualization, and you will find Venn diagrams at the intersection.

https://static.scientificamerican.com/dam/m/58baae5d2cfe435/original/venn-diagram_graphic_leadImage.png?m=1736869791.798&w=1200

2025-01-16 17:50:00