What the “year of democracy” taught us, in 6 charts

It was announced as the year of democracy. With more than one and a half billion elections in 73 countries, 2024 offers a rare opportunity to take the social and political temperature of almost half the world’s population.

The results are now in, and they have brought a damning verdict to the holders of public offices.

The incumbent in each of the 12 developed Western countries that held national elections in 2024 lost the share of the vote in the vote, the first time this has happened in almost 120 years of modern democracy. In Asia, even the hegemonic governments of India and Japan have not been spared the ill wind.

Incumbent or otherwise, centrists were often the losers, as voters rallied behind radical parties on either side. The populist right in particular surged ahead, fueled in significant part by a rightward shift among young people.

The results paint a picture of angry voters chastened by record inflation, tired of economic stagnation, unsettled by rising immigration, and increasingly disillusioned with the system as a whole.

In a sense, the year of democracy has produced a cry that democracy does not work anymore, with the young generation, many voting for the first time, sending some of the strongest reproaches against the establishment.

On average in the developed worldthe incumbent’s vote share fell by seven percentage points in 2024, an all-time record and more than double the decline as electorates punished elected officials after the global financial crisis.

The variety of countries producing similar results points to a common undercurrent, with inflation the obvious culprit.

In 2024, high and rising prices were the main concern of the public in the vast majority of countries that went to the polls. While recessions are very unpopular, their impacts are unevenly distributed. Inflation hurts everyone.

But if the crisis of the cost of living acted as a handicap for the incumbents, a closer look across different countries and regions shows that it was far from the only driver of discontent.

The biggest backlash against a sitting government has come in Britain, where the Conservatives’ charge sheet includes not only high prices, but a corruption scandal, a crisis in the provision of public health care, an economic shock self-inflicted and a sharp spike in immigration.

Across the channel in France, President Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to defend the populist right by calling early legislative elections backfired. The resulting political chaos has yet to be fully resolved months later.

In India, Narendra Modi’s formidable Bharatiya Janata Party secured a narrow victory but lost its parliamentary majority, struggling to stem the tide of discontent over the growing disconnect between strong economic growth and weak job creation. jobs

This was particularly pronounced among young people, whose unemployment rate rose to almost 50 percent before the election, according to data from the Indian Economy Monitoring Center.

Even the exceptions to the anti-incumbent wave are less anomalous when considered in the context of the other central themes of the year’s political changes.

In Mexico and Indonesia respectively, Claudia Sheinbaum and Prabowo Subianto each improved on the margin of the sitting president. In both cases, they ran broad campaigns promising continuity with their anti-elitist predecessors, illustrating the near-universal success of populists over the past twelve months. Prabowo also relied heavily on the dominance of the newcomer social media landscape, another common theme.

Seen worldwide, the weak performance of centrist parties and the march of populists, especially to the right, was as strong a theme as the anti-incumbent wave, perhaps stronger.

Even the victory of the Labor party in Great Britain is no exception here, since it won this year with fewer votes than in either of the two previous elections it lost. And a few months after a stunning victory, opinion suddenly turned against the party and the leader.

The French public’s irritation with Macron and his centrist party, meanwhile, reflects the broader global mood of disillusionment with the political establishment, and the sense that elected officials they either don’t know or don’t care what ordinary people think.

Although it came up short of its hoped-for victory, the 15-point swing achieved by France’s Rassemblement National in the parliamentary elections was the largest recorded by any party in any developed country this year. The second, third and fourth biggest gains of the year were all from right-wing populists such as Austria’s Freedom party, Britain’s Reform UK and Portugal’s Chega.

This speaks to the fact that immigration has been a growing concern in the developed world in recent years, and was one of the key issues on the minds of voters as they went to the polls.

Where conservative parties have lost ground, it has usually been the parties that flanked them on the right that have been the main beneficiaries. The success of Nigel Farage’s Reform in the United Kingdom in the exploitation of conservative voters in Britain has been largely attributed to the failure of the latter to meet his promise to reduce the number of immigration.

But anti-establishment successes are not limited to the right. The Greens in the United Kingdom were one of a handful of radical left parties that still gained ground as voters disillusioned with a stale center broke in both directions.

While the timing and magnitude of the anti-incumbent wave point primarily to the short-term shock of higher prices, the populist surge looks more like the continuation—or perhaps the acceleration—of a tendency which has been played in an increasing number of countries over two decades at least.

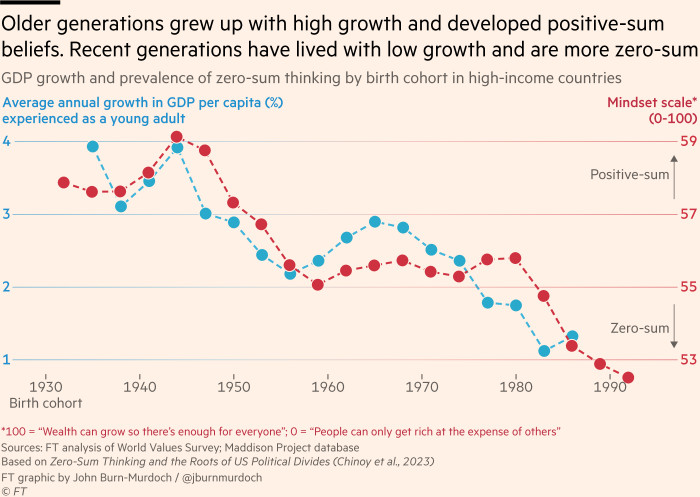

A prominent theory for why we see this developed was presented in an influential paper published earlier this year by a team of Harvard economists, who found that people who grow up in a background of weaker economic growth and less intergenerational progress are more likely to see the world as a zero sum, where one person’s gain must come to another. cost

The steady decline in upward economic mobility in rich countries could thus explain much of the rise of these views, which tend to be associated with the support of parties and politicians on the left and right who promise to tear up the existing system or protect it against external threats.

Another possibility is that dramatic changes in the media landscape over the past two decades have played a role in eroding long-standing norms against populist rhetoric and talking points. The emergence of social media has made it easier for political outsiders to speak directly to the public, leveling a playing field that had previously tilted towards established figures and parties.

Under the surface of the headline results, one of the most striking patterns seen in country after country has been the rise in support for the populist right among young people.

In Britain, support for Reform is now higher among men in their late teens and early twenties than among those in their thirties, and a marked gender gap has opened up between more young voters. A very similar pattern can be seen in the United States, where young people have also suddenly turned to Donald Trump in November, and the same pattern appears in much of Europe.

In particular, it seems that there is a lot of room for this trend to continue: the part that says they plan to vote for the radical right is even higher than those who already have.

Such a pronounced change is astonishing, but it is not without plausible explanation. If dissatisfaction with economic stagnation leads to zero-sum attitudes, few groups have experienced such flatlining as young people, whose relative socio-economic status has been constant decline through the west.

But it is not only young people who move to extremes. Young women in the United States have also turned to Trump, while in the United Kingdom many have switched to the Greens.

This is suitable with research from polling firm FocalData earlier this year, which found young people were far more likely than their elders to support a hypothetical national populist party, and a 2020 study who found satisfaction with democracy in the developed West declining more and faster among young adults than any other group.

All the indications are like this the two defining trends of 2024 are poised to continue next year. The latest polls show that the incumbent governments of Australia, Canada, Germany and Norway are all on course to lose power in the coming months.

And in most of these countries, it is once again the populist right that seems to be making the biggest gains. Norway’s right-wing populist Party of progress He currently leads after finishing fourth in 2021, and Germany’s AfD are currently polled in second place.

The crisis of acute inflation may be over, but with tenaciously weak economic growth, widening generational wealth and a fragmented media, 2024 may prove less an anomaly than a particularly jagged point in a downward trend.

https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/https%3A%2F%2Fd1e00ek4ebabms.cloudfront.net%2Fproduction%2F67b7c001-515a-418e-9f27-b00f2de08a4b.jpg?source=next-article&fit=scale-down&quality=highest&width=700&dpr=1

2024-12-30 05:00:00